Targeting a triple bottom-line: financial, environmental and social returns

What is Impact Investing?

Impact investing integrates financial returns with positive social or environmental impact. This impact may be quantified in terms of access to products and services, or economic opportunities for excluded communities, such as affordable mortgages to poor households or jobs for rural women. Environmental impact can be measured in terms of the volume of CO2 emissions saved. In 2020, the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) pegged the size of this market at USD 715 billion.

Reflecting on investing trends of 2020, an aspiring impact fund manager noted that global institutional investors invested USD 288 billion in sustainable assets last year.

“I believe that this is the beginning of a long but rapidly accelerating transition – one that will unfold over many years and reshape asset prices of every type. We know that climate risk is investment risk. But we also believe the climate transition presents a historic investment opportunity.”

- Larry Fink, CEO at the time of the largest asset manager in the world Blackrock, managing USD 8.7 trillion

When IRR meets Impact

Investing is premised on the relationship between risk and expected return, or IRR - internal rate of return. To earn a higher return, in general, you must hold riskier assets. Risk –simply, the likelihood of losing money - is viewed as volatility (bitcoin) or illiquidity (venture capital or real estate). Impact investors take a broader view of risk and return. Not only are financial returns important, but returns could also include quantifiable outcomes like CO2 saved, jobs created, or low-cost houses financed. Risk may require an assessment of second or third order impact of investment decisions: could lending to financially excluded households today result in an over-indebtedness crisis a decade later? Does this rural hospital, which generates hundreds of local jobs, have the expertise to safely dispose biological waste?

At the core of impact investing lies the belief that markets, with appropriate safeguards, can deliver positive outcomes at scale; that social enterprises will reinvest earnings to expand, and achieve operating efficiencies; that investors will want to invest in these profitable businesses, thus kicking off a virtuous cycle of investment and impact. Along the way, jobs are created, and governments earn taxes.

This is how things are meant to work, but occasionally, profit and purpose can come into conflict.

The Rise, Fall & Rise of Indian Microfinance

Pioneered by institutions like the Grameen Bank and SEWA in the 1970s, microcredit or microfinance is a form of collateral-free lending to poor households that are unable to access financial services for economic or social reasons. By the early 2000s, several Indian Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) reincorporated themselves as companies to become the earliest investments of the first impact investors. MFIs grew exponentially as capital was no longer a constraint, and SKS became the first MFI to list on the Indian Stock Exchanges in 2010. For investors at the time, this was the perfect asset class - not only high-impact and high-yielding, but also impervious to the turmoil of the subprime crisis, the collapse of investment bank Lehman Brothers or the Greek debt crisis, and also decoupled from the volatility in traditional capital markets. But then everything fell apart.

MFIs began to be accused of predatory lending amidst reports of borrower suicides in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, where the largest MFIs were based. It was alleged that MFIs pushed borrowers into debt-traps, with some poor households borrowing as many as 7-8 loans. The IPO was viewed as further evidence of profiteering. In October 2010, Andhra Pradesh passed a new law that effectively outlawed the sector overnight. Repayments on loans plummeted from over 99% to 0%. Investors lost money and thousands of rural jobs were destroyed.

The entry of private capital had undoubtedly helped MFIs expand their outreach, but this investor-led pursuit of growth and profit was at least partly responsible for the crisis. For me, there was a sense of déjà vu. My first (short-lived) job was structuring mortgage backed securities in London. Now, in my second job at an MFI halfway across the world in Hyderabad, a similar story was being replayed, even if the context and details were different.

But Indian microfinance experienced a resurrection after this which has been positive for Indian borrowers and MFIs alike: microfinance was now built on a foundation of client protection, risk management, transparency, and smarter regulation facilitated by better technology. Regulations now restrict the number loans that an MFI can lend to a household, but there is also a credit bureau which allows an MFI to instantly verify the borrower’s indebtedness levels. Impact investors continue to provide risk capital, but now also require MFIs to implement institutional safeguards like client protection and ESG policies, even when not required by law. And now some of the world’s best known institutional investors are enthusiastic investors in the sector today.

The Future of Impact Investing

The mainstreaming of microfinance has provided financial access to tens of millions of households across the world, but it has taken a few decades and several missteps to get here. It can provide a useful framework on how the market can be harnessed to deliver affordable healthcare or drinking water or clean energy to the world’s poorest populations. I believe that this is where the future of impact investing lies.

Through the 1990s, fuel stations in India had separate lines for leaded and unleaded petrol. By 2000, this was no longer required as regulations mandated the nationwide use of unleaded petrol. Hopefully, by the time my toddler is old enough to drive, the notion of fossil fuels in cars will feel like ancient history. Impact investing is like the unleaded petrol of my childhood: not everyone is doing it yet, and it costs a little more than the traditional alternative. But it’s also the future, and before we know it, all investing could be impact investing.

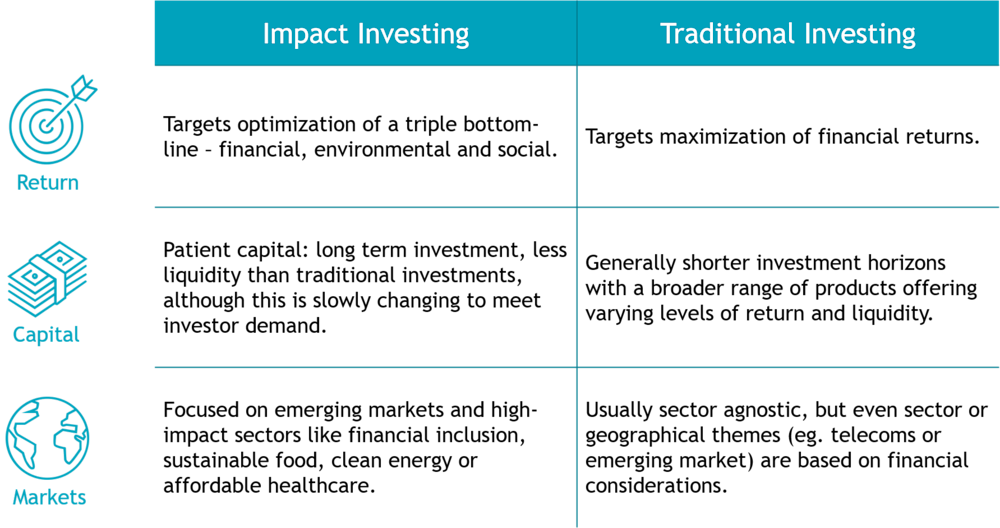

Top 3 Differences between Impact investing and Traditional investing

Sharad Venugopal

Sharad Venugopal is a Senior Investment Officer in the Financial Inclusion Debt team at responsAbility based in Mumbai. He has spent his career focused on debt across capital markets, micro and SME finance and impact investing. Sharad is a CFA Charterholder and has a M.Sc. in Economics from Warwick University.